Why dry-aged meat costs more – and can do more

What’s special about dry-aged meat

The process of dry aging (German: ‚Trockenreifung‘) has evolved into a true art form over the years, especially in the world of fine dining. Meat subjected to this aging process acquires unique flavor profiles and textures that distinguish it from fresh meat. Dry aging results in two main processes: moisture loss and enzymatic decomposition. Both processes significantly influence the flavor and texture of the meat.

Maturation takes time

Maturation typically takes place in special aging chambers ("dry agers") at temperatures between 0 and 2°C and a humidity of approximately 80–85% over a defined period, usually between 21 and 42 days. During the aging process, water evaporates from the meat, resulting in a concentration of flavors. Controlled air circulation ensures that the moisture escapes evenly and prevents the development of unwanted microorganisms.

The longer the meat ages, the more weight it loses—and the more intense its flavor becomes. During this time, the meat loses around 20–30% of its own weight through evaporation. The result is a piece of meat that, thanks to the aging process, is incredibly tender and flavorful. Aging beyond 42 days is, in principle, possible, but the actual benefits are controversial, and the taste may not appeal to every palate.

The question often arises as to how "old" a dry-aged steak is. However, this formulation is misleading: A dry-aged steak is not old, but rather matured. The aging process is a controlled refinement during which the meat develops its characteristic flavor and exceptional tenderness—rather than simply aging.

Enzymatic activity and flavor development

During the dry-aging process, enzymes present in the meat initiate the breakdown of proteins and fats. This creates amino acids and free fatty acids, which act as precursors for a variety of aromatic compounds. The enzyme processes begin within the first few days and are most intense in the first 7–10 days after slaughter. Therefore, it is important that the meat is placed in the aging chamber immediately after slaughter – something that is guaranteed at Kauf Dein Steak thanks to its own slaughterhouse and aging chambers. The enzymatic activity continues throughout the entire aging period, i.e., 3 to 6 weeks (or longer). As time passes, the processes slow down because a large portion of the easily digestible proteins and fats have already been broken down. It is precisely this controlled, slow breakdown of protein and fat that contributes significantly to the characteristic flavor of dry-aged meat: rich, nutty, and often with a clearly perceptible umami note *.

A “Buy Your Steak” dry-aged steak is usually aged for about six weeks to allow all natural processes the necessary time to develop the full flavor.

*"Umami" is a Japanese term that describes a savory, meaty, and particularly pleasant flavor. It is considered the fifth fundamental taste quality, alongside sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. Especially in dry-aged steaks, enzymatic activity ensures that this intense umami sensation is enhanced along with the natural flavor of the beef.

Perfect ripening climate thanks to salt wall

The natural regulation of humidity and the slightly disinfecting effect of salt create a perfect ripening climate without artificial additives. The meat matures in a controlled and hygienic manner, forming a protective crust and developing its distinctive aroma.

Anyone who wants to produce truly premium-quality dry-aged meat cannot do without a professional aging chamber with a salt wall. This makes the crucial difference between good and outstanding meat.

The salt wall

A salt wall is the heart of a professional dry-aging chamber. It creates the perfect microclimate essential for safe and consistent meat aging. During dry aging, the meat loses moisture, intensifying its flavor and tenderness. For this process to run smoothly, temperature, humidity, and air circulation must be precisely balanced. The salt wall naturally supports this process.

Their salt crystals draw excess moisture from the air and maintain a constant humidity level. At the same time, they release fine salt particles that have a mild disinfectant effect. This inhibits the growth of unwanted microorganisms – entirely without chemical additives. This combination creates a hygienic environment in which the meat can mature optimally.

In addition, the dry, salty air causes a protective crust to form on the meat's surface. This protects the interior of the piece of meat and intensifies the flavors. The result: a uniquely nutty flavor and a buttery texture that makes dry-aged meat so incomparable. The costs of setting up a professional aging chamber are considerable: The salt wall alone in the Buy Your Steak aging chambers costs around €100,000!

A salt wall is much more than just a visual highlight – it is the key to refining meat to the highest standards.

Decay vs. maturation

The enzymatic activity during dry aging affects not only the flavor but also the texture. The dry aging process should not be confused with putrefaction, which occurs when bacteria and microorganisms break down meat. Dry aging is a controlled enzymatic decomposition process: enzymes in the meat are broken down, making it more tender and flavorful.

During the dry-aging process, a dark, dry crust (called a pellicle) forms on the surface of the meat, which acts as a natural protective layer to preserve the underlying meat during aging. Harmless noble mold fungi can colonize there, positively influencing the aging process and developing flavors. "Dry-aged" means matured, but not spoiled. So, it's not that dry-aged meat doesn't develop mold; rather, the mold is a tool for flavor that must be removed later. Certain bacterial strains and mold cultures thus contribute to perfect meat aging. For this reason, some butchers deliberately apply the noble mold cultures to the surface of the meat.

Other types of mold, however, are harmful and are primarily caused by poor hygiene. Distinguishing which mold is safe requires specialist knowledge and experience. If you don't have this, you should definitely avoid mold growth when aging your own meat. Whether mold actually improves the flavor is debatable, but one thing is clear: the longer the meat ages, the more likely it is to appear. At Kauf Dein Steak, we place the greatest emphasis on hygienic conditions, and our master butcher specializes in processing dry-aged meat. So you can be sure: Only the finest, inspected meat – guaranteed mold-free – will end up on your plate.

The advantages of dry aging

The benefits of dry aging are manifold: it not only promotes a richer, more concentrated flavor, but also an impressive tenderness that elevates the culinary experience to a new level.

Although dry-aging requires an investment of time and resources, the result is undoubtedly a delicacy of unparalleled quality. In a world where authenticity and quality are increasingly valued, dry-aging stands as a shining example of culinary excellence.

Fresh

Dry-aged

Dry aging is best suited to high-quality beef with exceptional tenderness, fine grain, and beautiful marbling. Below, we present the five most well-known and commonly used cattle breeds for this aging process.

Best meat for dry aging

Wagyu

Wagyu

Particularly well-known is the Wagyu , a Japanese cattle breed that is valued worldwide for its exceptionally finely marbled meat. The name "Wagyu" literally means "Japanese cattle" ("wa" = Japan, "gyu" = beef). It is characterized by the extremely fine intramuscular fat structure, which gives the meat its unique tenderness and intense flavor. The most famous variety is the strictly controlled Kobe beef from the Hyōgo region. There are also other high-quality lines such as Matsusaka and Ōmi. While the beef was originally bred exclusively in Japan, there are now also programs in Australia, the USA and Europe. The meat from these Wagyu cattle is somewhat cheaper than that of the original Japanese animals, which are subject to particularly strict quality controls.

Original Japanese Wagyu, such as Kobe beef, can cost up to €400–600 per kilogram. Dry-aged Wagyu is unaffordable for most consumers due to the additional weight loss caused by dry aging.

For this reason, Wagyu is often offered as a crossbreed – the so-called Wagyu F1. "F1" refers to the first generation of a cross ( F1 = first filial generation ) between a purebred Wagyu and another breed of cattle. The goal of this crossbreed is to combine the pronounced intramuscular fat marbling of Wagyu with the performance-related characteristics of the other breed – such as faster growth or higher slaughter yield.

Iberico

Iberico

Occasionally, the term "dry-aged Iberian beef" is used in marketing. However, there is no taxonomically defined Iberian beef; strictly speaking, the term "Iberico" is reserved for the Iberian pig breeds used to produce "Jamón Ibérico." "Iberico beef" generally refers to the Galician Rubia Gallega cattle breed, and sometimes also to other indigenous breeds of the Iberian Peninsula, such as Retinta or Morucha. These animals are kept outdoors in northern Spain. They spend most of their lives in the highlands, where they are fed a natural diet of grasses, herbs, and sometimes chestnuts.

A characteristic of this farming method is the animals' comparatively long lifespan (8–15 years), as they are often initially used as dairy cows or working animals before being used for meat production. The meat exhibits pronounced marbling due to the high intramuscular fat content and a golden-yellow fat color due to the diet. Due to the combination of the breed's rarity, long rearing period, and high sensory value, this meat is considered a delicacy. Prices are significantly above average: individual steak cuts can reach up to €350 per kilogram.

Simmental

Simmental

Simmental cattle are one of the oldest cattle breeds. They originate from the Simmental Valley in the Bernese Oberland (Switzerland) and have been selectively bred since the Middle Ages. Like the Galician Rubia Gallega (often referred to as "Iberico cattle"), the breed is a dual-purpose cattle breed, bred for both milk production and meat. The meat is considered high-quality and established in the premium segment. It is characterized by a somewhat stronger grain, yet remains exceptionally tender and has particularly pronounced marbling—even more so than that of Angus cattle. The harmonious interplay of fat and muscle ensures an incomparably juicy and aromatic flavor experience. Especially when combined with dry aging, Simmental meat develops an intense, buttery, nutty aroma.

Due to its availability and consistently high meat quality, it is valued by top chefs and meat lovers alike. Due to its worldwide distribution, Simmental beef is more readily available than rare native breeds (e.g., Wagyu or Rubia Gallega), but remains highly sought after in the gourmet sector due to its sensory qualities. Its price ranges from mid- to high-end, depending on the cut and aging process (usually between €60–80/kg, significantly higher for specialty cuts or dry-aged meats).

Angus

Angus

The Black Angus cattle originated in Scotland and are now one of the world's most famous beef cattle breeds. They are known for their robustness, adaptability, and consistent meat quality. Angus cattle are considered a medium- to large-framed cattle breed. Their weight varies depending on sex and age: Angus cows typically weigh between 550 and 700 kilograms, while adult Angus bulls can weigh between 850 and 1,200 kilograms.

Angus beef boasts even, fine marbling and a mild, juicy flavor. Compared to more heavily marbled breeds like Wagyu or Simmental, however, it is less opulent—Wagyu, in particular, is characterized by a significantly higher intramuscular fat content, delivering a more intense butteriness and tenderness. However, those who prefer a genuine, robust beef flavor without excessive fat will find Angus a very good choice.

In terms of quality, Angus beef is on a par with Simmental and Charolais. These three traditional breeds produce meat that delights connoisseurs with its fine structure, balanced marbling, and robust flavor—at the premium level, yet still affordable. Angus beef is well-suited to dry aging: During aging, the meaty notes intensify, the texture becomes more tender, and a nutty, buttery character develops without losing its clear aromatics. Price-wise, Angus beef is in the mid- to upper-end segment (approximately €40–70/kg), depending on the cut and aging duration, placing it in a similar category to Simmental and Charolais, but significantly below Wagyu.

Charolais

Charolais

The Charolais cattle is one of the most well-known beef cattle breeds in the world. It originated in the Charolais region of Burgundy, France, and was selectively bred as early as the 18th century. Today, it is one of the most important beef cattle breeds in Europe and is also widespread in North and South America, Australia, and Africa. The breed was primarily selected for meat production, making it a classic beef cattle breed and—unlike dual-purpose breeds—rarely used for milk production. Charolais beef is characterized by fine grain, low fat content, and a strong beef flavor. Compared to heavily marbled breeds (e.g., Wagyu or Rubia Gallega), the intramuscular fat is less pronounced. This makes Charolais beef particularly suitable for connoisseurs who prefer an authentic, unadulterated beef flavor.

Charolais beef is particularly well-suited for dry aging: Thanks to its fine muscle structure and low water content, the meat matures evenly, developing intense, aromatic notes and becoming even more tender. The result is a buttery, nutty, yet clearly defined flavor profile that is highly valued in fine dining. Due to its widespread distribution, Charolais beef is in the upscale, but not the absolute luxury, segment. Prices typically range between €40–60/kg, although they can be higher for special cuts or longer maturation.

Particularly well-known is the Wagyu , a Japanese cattle breed that is valued worldwide for its exceptionally finely marbled meat. The name "Wagyu" literally means "Japanese cattle" ("wa" = Japan, "gyu" = beef). It is characterized by the extremely fine intramuscular fat structure, which gives the meat its unique tenderness and intense flavor. The most famous variety is the strictly controlled Kobe beef from the Hyōgo region. There are also other high-quality lines such as Matsusaka and Ōmi. While the beef was originally bred exclusively in Japan, there are now also programs in Australia, the USA and Europe. The meat from these Wagyu cattle is somewhat cheaper than that of the original Japanese animals, which are subject to particularly strict quality controls.

Original Japanese Wagyu, such as Kobe beef, can cost up to €400–600 per kilogram. Dry-aged Wagyu is unaffordable for most consumers due to the additional weight loss caused by dry aging.

For this reason, Wagyu is often offered as a crossbreed – the so-called Wagyu F1. "F1" refers to the first generation of a cross ( F1 = first filial generation ) between a purebred Wagyu and another breed of cattle. The goal of this crossbreed is to combine the pronounced intramuscular fat marbling of Wagyu with the performance-related characteristics of the other breed – such as faster growth or higher slaughter yield.

Occasionally, the term "dry-aged Iberian beef" is used in marketing. However, there is no taxonomically defined Iberian beef; strictly speaking, the term "Iberico" is reserved for the Iberian pig breeds used to produce "Jamón Ibérico." "Iberico beef" generally refers to the Galician Rubia Gallega cattle breed, and sometimes also to other indigenous breeds of the Iberian Peninsula, such as Retinta or Morucha. These animals are kept outdoors in northern Spain. They spend most of their lives in the highlands, where they are fed a natural diet of grasses, herbs, and sometimes chestnuts.

A characteristic of this farming method is the animals' comparatively long lifespan (8–15 years), as they are often initially used as dairy cows or working animals before being used for meat production. The meat exhibits pronounced marbling due to the high intramuscular fat content and a golden-yellow fat color due to the diet. Due to the combination of the breed's rarity, long rearing period, and high sensory value, this meat is considered a delicacy. Prices are significantly above average: individual steak cuts can reach up to €350 per kilogram.

Simmental cattle are one of the oldest cattle breeds. They originate from the Simmental Valley in the Bernese Oberland (Switzerland) and have been selectively bred since the Middle Ages. Like the Galician Rubia Gallega (often referred to as "Iberico cattle"), the breed is a dual-purpose cattle breed, bred for both milk production and meat. The meat is considered high-quality and established in the premium segment. It is characterized by a somewhat stronger grain, yet remains exceptionally tender and has particularly pronounced marbling—even more so than that of Angus cattle. The harmonious interplay of fat and muscle ensures an incomparably juicy and aromatic flavor experience. Especially when combined with dry aging, Simmental meat develops an intense, buttery, nutty aroma.

Due to its availability and consistently high meat quality, it is valued by top chefs and meat lovers alike. Due to its worldwide distribution, Simmental beef is more readily available than rare native breeds (e.g., Wagyu or Rubia Gallega), but remains highly sought after in the gourmet sector due to its sensory qualities. Its price ranges from mid- to high-end, depending on the cut and aging process (usually between €60–80/kg, significantly higher for specialty cuts or dry-aged meats).

The Black Angus cattle originated in Scotland and are now one of the world's most famous beef cattle breeds. They are known for their robustness, adaptability, and consistent meat quality. Angus cattle are considered a medium- to large-framed cattle breed. Their weight varies depending on sex and age: Angus cows typically weigh between 550 and 700 kilograms, while adult Angus bulls can weigh between 850 and 1,200 kilograms.

Angus beef boasts even, fine marbling and a mild, juicy flavor. Compared to more heavily marbled breeds like Wagyu or Simmental, however, it is less opulent—Wagyu, in particular, is characterized by a significantly higher intramuscular fat content, delivering a more intense butteriness and tenderness. However, those who prefer a genuine, robust beef flavor without excessive fat will find Angus a very good choice.

In terms of quality, Angus beef is on a par with Simmental and Charolais. These three traditional breeds produce meat that delights connoisseurs with its fine structure, balanced marbling, and robust flavor—at the premium level, yet still affordable. Angus beef is well-suited to dry aging: During aging, the meaty notes intensify, the texture becomes more tender, and a nutty, buttery character develops without losing its clear aromatics. Price-wise, Angus beef is in the mid- to upper-end segment (approximately €40–70/kg), depending on the cut and aging duration, placing it in a similar category to Simmental and Charolais, but significantly below Wagyu.

The Charolais cattle is one of the most well-known beef cattle breeds in the world. It originated in the Charolais region of Burgundy, France, and was selectively bred as early as the 18th century. Today, it is one of the most important beef cattle breeds in Europe and is also widespread in North and South America, Australia, and Africa. The breed was primarily selected for meat production, making it a classic beef cattle breed and—unlike dual-purpose breeds—rarely used for milk production. Charolais beef is characterized by fine grain, low fat content, and a strong beef flavor. Compared to heavily marbled breeds (e.g., Wagyu or Rubia Gallega), the intramuscular fat is less pronounced. This makes Charolais beef particularly suitable for connoisseurs who prefer an authentic, unadulterated beef flavor.

Charolais beef is particularly well-suited for dry aging: Thanks to its fine muscle structure and low water content, the meat matures evenly, developing intense, aromatic notes and becoming even more tender. The result is a buttery, nutty, yet clearly defined flavor profile that is highly valued in fine dining. Due to its widespread distribution, Charolais beef is in the upscale, but not the absolute luxury, segment. Prices typically range between €40–60/kg, although they can be higher for special cuts or longer maturation.

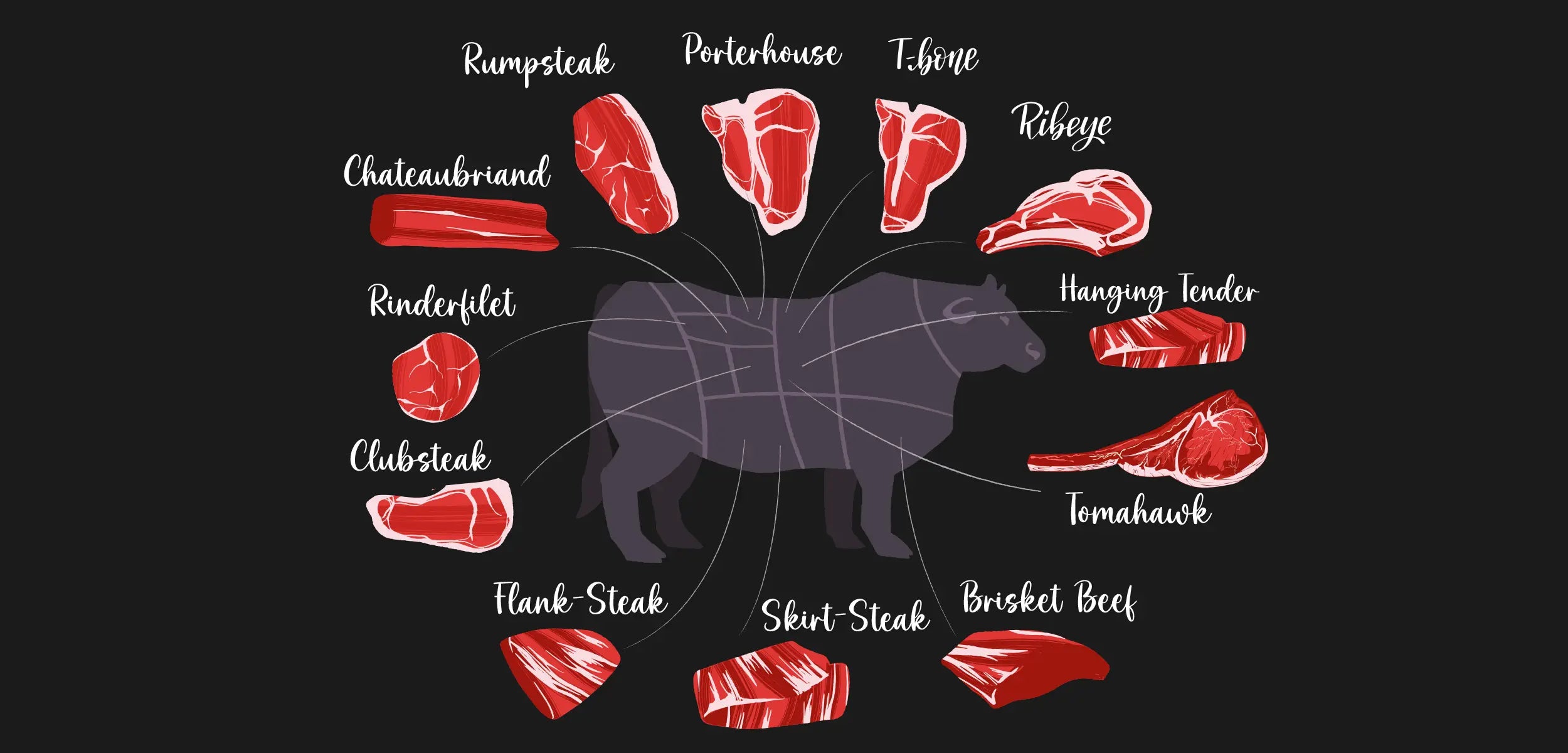

Steak and Cuts Guide

From tender fillet to finely marbled ribeye, every cut of beef has its own character, signature texture, and perfect preparation. Our beef cut chart shows you where each cut comes from.

Precious pieces that deserve time

Which cuts of beef are best suited for dry aging?

The most popular cuts are the back cuts, such as sirloin, ribeye, entrecôte, or prime rib. These cuts feature pronounced intramuscular marbling, which ideally supports the aging process and provides an intense, characteristic flavor. These cuts are used to produce classic dry-aged steaks such as T-bone, porterhouse, and tomahawk. They not only impress with their impressive appearance, but also develop a distinctive flavor and exceptional tenderness during aging.

Less suitable, however, are cuts with less marbling or typical braised cuts such as brisket or beef shank . Poultry and pork are also rarely dry-aged, as their meat structure and shelf life do not meet the requirements of this complex aging process. The dry-aged pluma steak is an exception. The pluma is a heavily marbled, thin, triangular piece of meat from the pork loin. The term 'pluma' comes from Spanish and means 'feather' – a reference to the characteristic triangular shape of this cut.

In short: The ideal meat for dry aging is a well-marbled beef loin with bones – the basis for our exclusive premium steaks.

When you buy your steak, we always dry-age whole loins and only cut the steaks when they are sold, so you can enjoy the highest level of freshness and full flavor.

✅ Best suited:

Especially back cuts of beef – such as roast beef, ribeye/entrecôte or prime rib

Highly marbled meat – the intramuscular fat protects during the maturation process and intensifies the aroma

Cuts on the bone (e.g. T-Bone , Porterhouse or Tomahawk ) – the bone supports the maturation and gives additional flavor

Large pieces of meat (Primals) – are better than small pieces because they dry out less quickly during the aging process

❌ Less suitable:

- Meat with low marbling → dries out quickly

- Braised cuts (e.g. veal, breast) → are not suitable as they benefit from long cooking times and not from maturing

- Poultry and pork are almost never offered dry-aged because the risk of spoilage is too high and the meat structure is unsuitable

- Smaller individual pieces or steaks without bones → these lose moisture too quickly and become tough instead of tender

- Low quality meat → even dry aging cannot compensate for the lack of meat quality

Distinguishing features of dry-aged meat

"Dry-aged" is a term that makes meat connoisseurs and meat lovers' eyes sparkle, is discussed in many forums, and is now even practiced in some private households.

With the method of dry aging on the bone, a form of meat aging that has been known for a long time is returning – but is now perfected through technology as well as breed, genetics, feeding and husbandry.

Dry-aged meat represents the highest level of steakmaking. The controlled aging process develops an intense flavor, unparalleled tenderness, and a texture that connoisseurs appreciate. Time, craftsmanship, and the highest quality meat – that's what makes dry-aged meat so special.

Due to the loss of water during dry aging, the flavors become concentrated.

Typical: nutty, buttery and slightly earthy notes.

Natural enzymes break down muscle and connective tissue, which makes the meat particularly tender.

Maturation takes place in our special climate chambers with controlled temperature, humidity, and air circulation. Artisan aging requires patience, expertise, and time.

Selection of the best cuts of meat, mostly from beef loin with high marbling .

Refined exclusively through time, air, salt walls and craftsmanship – no use of marinades or artificial flavors.

Longer maturation time (21 – 42 days or more) makes it a rare, high-priced gourmet product.

Firm but tender consistency with a characteristic delicate “bite” that is clearly different from fresh meat.

Less water content means more intense meat flavor and stronger umami notes.

The Maillard aroma

The so-called Maillard aroma—also known as roasted aroma—is created by theMaillard reaction . This is a chemical reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars that occurs when food is heated. It is responsible for the appetizing browning as well as the complex aromas and flavors we associate with fried, baked, or roasted foods.

Crispy crust

Moisture is the biggest enemy of a crispy crust. A dry surface ensures the steak browns faster and more evenly, meaning it spends less time in the pan—significantly reducing the risk of overcooking. Paradoxically, a steak that's as dry as possible produces the juiciest results.

A taste that polarizes

Despite the popularity of dry-aged meat, it's important to note that its flavor isn't to everyone's liking. Some describe the taste as too intense or even "cheesy." It's a flavor often appreciated by experienced palates seeking depth and complexity.

Dry-aged meat is often described as the pinnacle of preparation, but it's actually not that difficult.

The preparation of dry-aged steaks

Because dry-aged meat has such a distinctive flavor, it's often recommended to prepare it very simply—especially if you're new to it. Keep the seasoning simple at first: a little salt (approx. 0.8–1% of the meat's weight) just before cooking, high heat, and a little pepper after cooking, if desired—that's usually all it takes to bring out the full flavor of this meat. Overseasoning could mask its unique taste. As you gain experience in cooking and develop a keen sense of taste, you can gradually add additional seasonings.

Before frying, dry-aged steaks should first be brought to room temperature. The immediate temperature change from chilling to high heat causes increased fluid and protein to escape, which can cause the surface of the meat to turn gray and dry out the steak. A resting period of at least 60 minutes at room temperature is therefore recommended. A dry-aged steak should also always be placed in the pan dry. Any water on the surface will evaporate first, preventing the development of intense roasting aromas (the Maillard flavor). Therefore, it is best to pat the meat thoroughly dry with a kitchen towel before frying.

Even after cooking, the steaks should rest for 3 to 5 minutes to allow the juices to distribute evenly throughout the meat, ensuring the final product is particularly tender and juicy. Only when serving should the meat be cut across the grain into 1–1.5 cm thick slices. For bone-in cuts, remove the meat along the bone before slicing.

Maturation creates the basis, preparation creates the character

The 7 best ways to prepare dry-aged meat

Dry-aged steaks are among the finest meat specialties of all – intense in flavor, incomparably tender in texture. To achieve their full potential, they depend not only on aging but also on proper preparation. We present seven different methods for perfectly preparing a dry-aged steak – from the classic grill to a cast-iron pan to modern techniques like sous-vide. This way, you're guaranteed to find the preparation method that best suits your taste.

More than just premium meat: Our dry-aged steak product pages feature recipes tailored to each cut – simply cook and enjoy!

Precisely frying steaks in a pan to an exact doneness requires experience. Too high a heat will burn the outside while the inside remains raw; too low a heat will cook the meat unevenly, and a strong crust won't form. It's crucial to adjust the pan temperature optimally to the thickness of the steak from the start—otherwise, the result can quickly be ruined.

A more reliable method is the combination of pan and oven: The steak is either first seared in the pan and then gently cooked in the oven, or conversely, first cooked in the oven and then briefly seared (see the sections "Reverse Cooking in the Oven" and "Forward Cooking in the Oven"). This allows the interior of the steak to be cooked much more precisely, and minor variations in heat are less significant.

If an oven is not available, dry-aged steaks can of course also be prepared entirely in a pan.

Dry-aged steaks require intense heat during preparation. Searing them in beef kidney fat or clarified butter—ideally in a cast-iron pan—creates intense roasted flavors, while the exterior of the meat develops a crispy crust.

Heat a cast-iron or heavy-gauge steel skillet over very high heat (5–8 minutes for electric/induction, 2–3 minutes for gas). The exact time depends on the thickness of the skillet and the power of the stovetop. Aluminum skillets are less suitable for searing, as they don't retain heat as well as cast iron, for example. Once the skillet is hot enough, add the beef suet and shortly thereafter, add the steak. Turn the meat every minute to ensure even browning and cooking.

To turn the steak, we recommend using only a spatula – a meat fork should be avoided as it will pierce the meat and cause valuable juices to escape.

For a “medium rare” steak, a total cooking time of about 2 minutes is sufficient, while for “medium well” it takes about 4 minutes.

Preparing a steak in the oven offers numerous advantages and reliably delivers perfect results for both professionals and beginners. The even and consistent heat allows the meat to cook particularly gently, reaching the desired degree of doneness without overcooking the exterior. The result is a juicy, flavorful steak with the ideal balance of a crispy crust and tender interior. This method also allows for relaxed preparation, allowing even multiple steaks to be cooked at the same time with consistent quality.

Reverse cooking

With reverse cooking, the steak is first gently cooked at a low temperature in the oven before being seared at the end. The name "reverse cooking" comes from the fact that it turns the traditional method on its head.

Historically, the advice was: Sear first, then continue cooking. This was usually justified by the claim that searing seals in juices. Today we know for sure: This isn't true. Searing doesn't seal in liquid; it simply adds flavor.

The temperature gradient within a piece of meat—the difference between the edge and the center—directly depends on how quickly energy is transferred into the meat. The higher the cooking temperature, the faster energy flows and the more unevenly the meat cooks. Conversely, the more gently the steak is heated, the more evenly it cooks. Starting cooking in a low-temperature oven minimizes overcooking. The result: a juicier steak.

Ideally, the process begins by placing the steak uncovered on a rack over a baking sheet in the refrigerator overnight. The circulating refrigerator air ensures a dry surface. The drier the surface, the faster and better the steak will brown. The next day, the entire baking sheet, including the rack, goes directly into the oven. Because the temperature rises slowly, reverse cooking is the only cooking method that allows you to safely transfer the meat directly from the refrigerator to the oven.

The meat is slowly and evenly brought to the desired core temperature in the oven at around 100–130°C. This gentle heat ensures that the steak cooks evenly from the inside out, without overheating the outside too quickly. Once the temperature is about 5–8°C below the desired core temperature, the crucial step begins: searing in a very hot pan or on the grill. This quickly develops an aromatic, crispy crust – the so-called Maillard aroma, which ensures intense flavor. The meat remains juicy and tender on the inside, while the perfect crust develops on the outside.

This is how you get one of the best-cooked steaks ever!

Dry-aged cuts at least 3–5 cm thick (e.g., ribeye, rump steak, T-bone/porterhouse) are ideal for grilling. Thicker steaks are more forgiving of temperature fluctuations and develop a more stable crust. Pat the meat thoroughly dry before grilling.

Set up a two-zone grill : a direct zone (very hot, for searing) and an indirect zone (moderate heat, for cooking).

- Let a full chimney starter glow through, pour the coals onto one side of the grill and open the vent wide.

- Preheat all burners for about 10 minutes, then set one side to high and the other to low to medium power.

Goal: As much heat as possible under the lid in the direct cooking area, and approximately 120–140 °C in the indirect cooking area. A cast iron grate is ideal for this.

Reverse cooking

Our recommendation – first cook gently, then sear

Store the steak uncovered on a rack in the refrigerator until ready to grill. This will allow the surface to dry slightly and brown more quickly. Place the dry steak in the indirect cooking zone and close the lid. Adjust the vent to maintain a temperature of 120–140°C. Slowly cook the steak to an internal temperature of approximately 45–48°C (approximately 20–35 minutes for a 4 cm thick steak, depending on the grill).

Then increase the temperature in the direct cooking zone to maximum. Grill the steak over direct heat, turning it every 30–45 seconds. The goal is an even, dark crust without burning. Briefly sear the fat and edges. Stop searing when the target internal temperature is reached (e.g., 55–57°C for medium-rare).

Serve immediately – ideally with a mild side dish that doesn't overpower the intense dry-aged flavor (e.g. grilled vegetables or a simple salad).

Forward cooking

First fry, then let it simmer indirectly

First, place the steak over direct heat and sear it vigorously for 60–90 seconds per side (lid open, turning frequently). Then transfer it to the indirect heat, close the lid, and cook at 120–150°C (258–300°F) to reach the target internal temperature. This method is faster but requires more timing.

Pepper, salt, and any spices should only be added after grilling—they burn easily at high heat and can have a bitter taste. If your grill is sticky, lightly brush the grill (not the steak) with high-heat oil (e.g., refined rapeseed or peanut oil).

Make sure the steak is always placed on the grill dry – moisture is the enemy of a perfect crust. If escaping fat causes flames, immediately move the steak to the indirect cooking zone and briefly close the lid. This will deprive the flames of oxygen.

Quick, frequent turning during searing distributes the heat more evenly, prevents black spots, and ensures a uniform crust. When gently simmering, work with the lid closed, and when searing, usually with the lid open – this gives you better control.

Remove the steak from the grill about 2°C before it reaches the target temperature, place it on a preheated board, and let it rest for 3-5 minutes. This allows the meat juices to distribute evenly throughout the meat while preserving the crust.

Typical cooking times for a 4 cm thick ribeye (for orientation):

- 20–35 minutes indirectly at 45–48 °C, then sear directly for a total of 2–3 minutes (turn frequently).

- Sear directly for 2 x 60–90 seconds, then cook indirectly for 6–10 minutes.

The times vary depending on the grill, wind, steak thickness and ambient temperature – the thermometer replaces the stopwatch!

Always ensure cleanliness: The separation of raw and cooked meat also applies to beef. Never leave steaks unattended over an open flame. For very dry-aged cuts, it's recommended to trim back any excess, oxidized fat before grilling—this will prevent flare-ups and bitter flavors.

Thinner steaks, such as flank steak or hanging tender, are also well-suited for the sous vide method. They cook quickly and can be prepared without drying out. However, dry-aged cuts with a thickness of at least 3–5 cm (e.g., ribeye, rump steak, T-bone, or porterhouse steak) are preferred. If necessary, trim dry edges and heavily oxidized fat sparingly. Pat the surface thoroughly dry—moisture is the enemy of a good crust.

The challenge with thinner steaks is that the inside cooks quickly during searing. Therefore, the thinner the steak, the lower the water should be (and thus farther from the desired internal temperature), and the shorter the final searing time.

In addition to standard utensils such as a pan, spatula, and core temperature probe, two devices have proven particularly helpful: a vacuum sealer and a sous-vide immersion heater. A sous-vide immersion heater (sous-vide circulator) heats the water in a pot or container to a precisely adjustable temperature and maintains it at a constant temperature. A built-in pump ensures even circulation. The user sets the desired temperature and often also the cooking time. Sous-vide cooking is also possible without these devices. However, if you plan to use this method regularly, it's a good idea to purchase both.

Place the steak in a heat-resistant vacuum bag. Optionally, you can add 1-2 thin slices of beef tallow or half a teaspoon of clarified butter, along with 1-2 sprigs of thyme or rosemary. Avoid moist marinades, as they dilute the flavor. If you have a vacuum sealer, vacuum seal the bag tightly without deforming the meat. Alternatively, use the "water displacement method" with a zippered bag: Almost seal the bag, slowly submerge it in water, squeeze out any air, and seal it completely. Make sure to leave as little air as possible in the bag.

Fill the container with hot tap water, insert the sous vide wand, and set the target temperature and, if necessary, the cooking time. Without a circulator, the temperature can also be controlled with a thermometer—but it will then have to be monitored and adjusted manually. Hang the bag so that the steak remains completely submerged. Weigh down the bag if necessary. Make sure the water can circulate around the bag. A lid or cover reduces evaporation and keeps the temperature stable. Turning is not necessary during cooking.

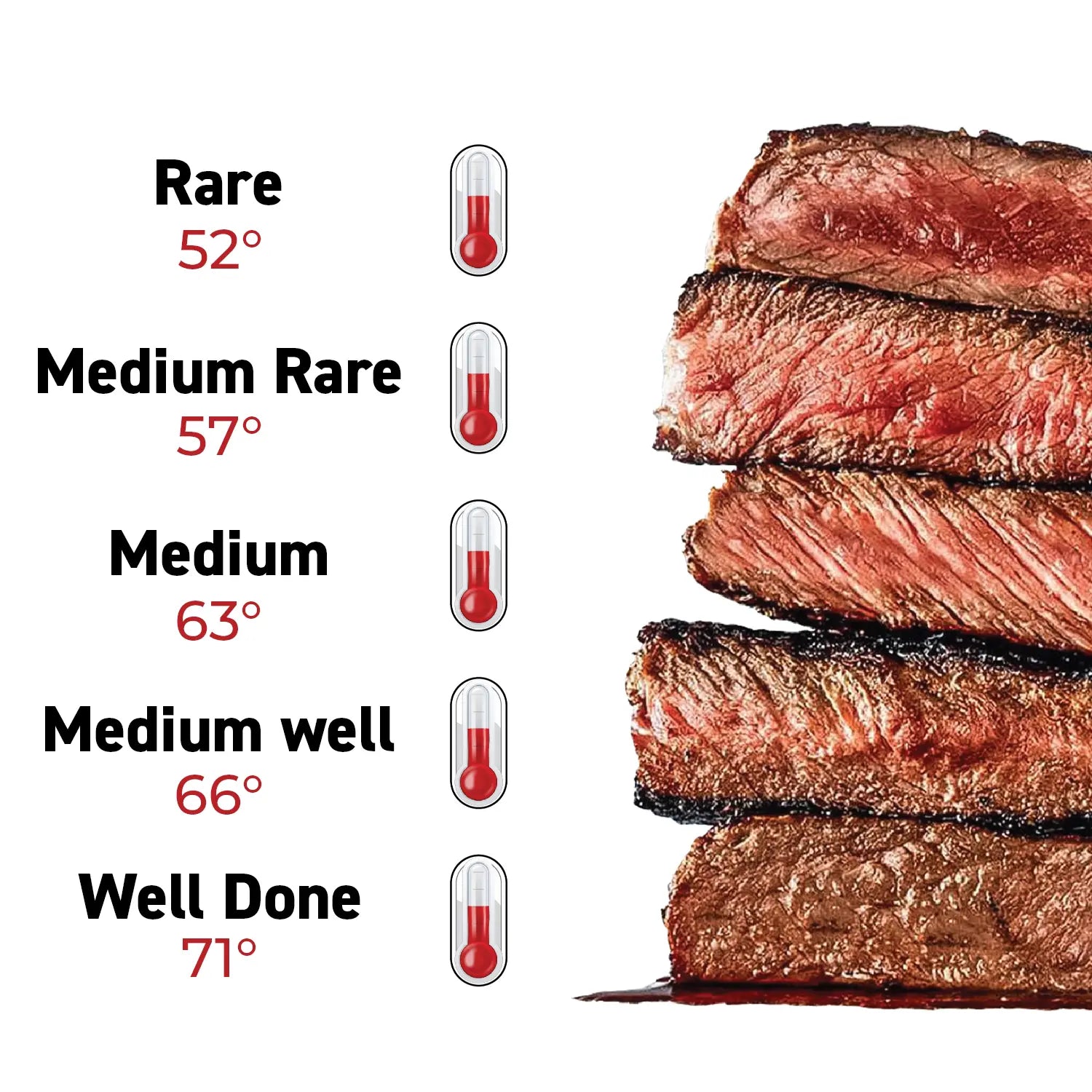

As a guide for the degree of cooking (core temperature = bath temperature):

- Rare: 50–52 °C

- Medium Rare: 55–57 °C

- Medium: 60–63 °C

- Medium Well: 65–67 °C

- Well done: 70°+

The exact cooking time depends on the thickness of the steak: For a steak about 3 cm thick, you should allow 1–2 hours, for 4 cm, 2–3 hours, and for 5 cm, 3–4 hours. Longer cooking times within this time frame are easily possible and ensure a particularly even result – as long as the temperature remains stable and does not deviate from the desired internal temperature.

For maximum crust without overcooking, place the steak in ice water (in the bag, of course) for 3-5 minutes after the bath and then pat it dry thoroughly.

This cools the surface, allowing it to brown longer during searing without overcooking the core. This is especially beneficial for thinner steaks. If you want to finish immediately, skip this step and pat dry extra carefully.

Heat a cast-iron or heavy-gauge steel skillet over very high heat (2–3 minutes on gas, 5–8 minutes on electric/induction). Add a thin film of high-heat oil (e.g., refined rapeseed or peanut oil). Place the dried steak in the skillet and cook for 45–60 seconds per side, turning every 20–30 seconds for even browning. Briefly sear the edges and fat layer.

For very thick cuts (e.g., tomahawk or porterhouse), it's worth bone-cutting the meat after sous vide cooking and then searing each loin portion separately. In the last 20 seconds, you can add a little clarified butter and, optionally, garlic or thyme, and "baste" the steak (baste it with fat). This finish typically raises the internal temperature by 1–2°C.

Sous-vide cooked steaks do not require a long resting period – 2-3 minutes on a warm board are sufficient before serving.

The plancha originated in Spain and literally means "metal plate." Traditionally, it was used outdoors over an open fire, but today it is also frequently used with gas or electricity. Its high heat, even heat distribution, and direct contact with the meat ensure that proteins and sugars caramelize particularly intensely without the meat drying out. The result is a rich crust, while the flavor remains unadulterated – completely without smoke or flames. The plancha is therefore an ideal, purist method for experiencing the pure character of a dry-aged steak. While it functions similarly to a pan, the latter is usually smaller, overheats more quickly, and distributes heat less evenly. Furthermore, the plancha is predominantly used outdoors – thus combining culinary enjoyment with a special feeling of freedom.

Steak preparation on the plancha

A thick-cut, dry-aged steak such as a ribeye, entrecôte, or porterhouse is ideal for cooking on the plancha. It should be taken out of the refrigerator at least 60 minutes before grilling to allow it to reach room temperature. The plancha itself must be preheated to a very high temperature – ideally between 250 and 300 degrees Celsius. Minimal use of high-temperature oil (e.g., refined peanut or avocado oil with smoke points above 220 °C) prevents sticking. Coarse sea salt and pepper are added only after cooking to prevent the seasoning from burning. Once the plate is heated, the steak, patted dry, is placed on the plate. Depending on the desired degree of doneness, it should cook for one to three minutes per side without constantly turning it over to develop a golden brown crust. For very thick cuts, the steak can then be left to cook on the cooler side of the plate or in the oven at a lower temperature. Before serving, it should rest for three to five minutes so that the meat juices are evenly distributed.

The strength of the plancha lies in its direct and even contact heat. Unlike a grill grate, where heat is applied only in specific spots, the meat rests completely on the plancha. This creates a consistent and intense Maillard reaction, which ensures strong roasting aromas and the characteristic crust. Furthermore, the dry-aged flavor isn't overpowered by smoke or extreme heat, but remains pure and unadulterated.

Cooking on a plancha is the ideal method for anyone who wants to experience the pure character of a dry-aged steak. It creates a rich crust while preserving the meat's succulence and flavor. It's versatile, as side dishes can also be prepared on the same plate. However, it requires a high-quality, solid plate, as thinner models distribute heat unevenly.

The Salamander's greatest strength lies in its extremely high temperature performance, which enables rapid crust formation. This creates a pronounced Maillard reaction, producing intense roasted aromas and a caramelized surface. The dry-aged flavor is particularly enhanced by this preparation, as the robust crust creates a wonderful contrast to the nutty, buttery meat flavor. Dry-aged beef in the Salamander broiler unfolds a whole new level of flavor! The intense caramelization caused by the extremely high heat, combined with the aged flavor, creates an incredibly intense flavor.

Before the dry-aged steak goes into the salamander, several requirements must be met. The steak should be at least 3 cm thick to prevent it from drying out during the process. The salamander grill itself must have a high temperature output – temperatures of at least 1,000 °C are optimal (and even higher), as this is the only way to achieve a strong crust. However, most salamander grills for home use don't get hot enough to achieve this result. They lack the power to keep up with the temperatures of professional salamanders. Ventilation in ordinary households is often inadequate.

Steak preparation in the Salamander grill

The steak should be taken out of the refrigerator well in advance of cooking so that it reaches room temperature – this ensures even cooking results. The steak is first lightly seasoned with coarse sea salt. Pepper and other spices should only be added after cooking, as they can burn at high temperatures and leave a bitter taste. If you like, you can lightly rub the meat with a neutral oil to improve heat transfer, but this is not necessary for the salamander. The steak is placed on a suitable grill or grill rack that allows direct heat application from above.

The salamander broiler generates extreme heat from above, which caramelizes the steak in a very short time. Therefore, unlike cooking on a regular grill or in a pan, the salamander is primarily suitable for initiating the Maillard reaction and crust formation, not for the complete cooking process. To achieve the desired doneness, a two-stage process is recommended. This means that you also need to use the oven to achieve the perfect doneness. There are basically two processes: forward cooking (first a strong sear, followed by a low-temperature finish) and reverse cooking (first gentle cooking, followed by a brief high-temperature finish). Reverse cooking has proven particularly effective for the salamander grill.

When reverse cooking, the steak is precooked in a preheated oven at a moderate temperature (120–140°C) to 2–3 degrees below the desired doneness (e.g., medium-rare with an internal temperature of approximately 54–56°C). A meat thermometer is the most important tool for achieving precise results.

The salamander broiler is preheated to a temperature of at least 1,000°C, or higher if powerful enough. The meat is then placed approximately 2–3 cm below the heating elements. For a nice crust, a cooking time of 30–90 seconds per side is usually sufficient, depending on the thermal performance of the appliance and the desired degree of browning. The steak is then flipped to ensure an even Maillard reaction on both sides. Due to the significantly higher temperature, precise control of the process is required to avoid overcooking or burning the product.

Once the steak has reached the desired internal temperature, let it rest for 3–5 minutes. This time allows the juices to distribute evenly throughout the steak, making it juicier and more flavorful. The meat can now be refined with freshly ground pepper, a little fleur de sel, or a touch of herb butter. Carve across the grain to ensure a tender mouthfeel.

Cooking in a salamander grill requires experience, as there's a risk of burning the steak or cooking it unevenly. A steak that's too thin will dry out very quickly. Furthermore, a professional salamander grill is expensive to purchase and requires a lot of space, which isn't always practical for home users.

Preparing a steak in the oven offers decisive advantages and makes it easier for both professionals and amateurs to achieve the perfect result.

Thanks to the even and consistent heat, the meat cooks particularly gently and reliably reaches the desired degree of doneness – without overcooking the exterior. The result is a juicy, flavorful steak with the ideal balance between a tender crust and a juicy interior. This method also allows for stress-free preparation, allowing even multiple steaks to be cooked at the same time with consistent quality.

Forward cooking

A proven technique for a juicy result is forward cooking : The steak is first seared in a pan and then gently cooked in the oven. Important: Always set the oven to top and bottom heat. Fan-assisted cooking is unsuitable for steaks, as it causes the meat to dry out.

The meat is seared briefly and vigorously on both sides in a very hot pan – unlike when simply pan-fried, this is only about 30 seconds per side (see the "Pan-Fried" section). The steak is then cooked in the oven at a lower temperature until the desired internal temperature is reached.

A temperature of 160–180°C is ideal for finishing the steak. If you don't want to miss the optimal cooking point, you can also let the meat cook at 80–100°C . While this increases the cooking time, this method is particularly gentle and error-tolerant.

Finally, season to your personal taste – this way, the full flavor comes out perfectly.

How do you eat dry-aged meat?

Dry-aged meat is eaten rare to medium-rare, with little frills and plenty of meaty flavor. As for side dishes, keep it simple. A few potatoes, vegetables, a dash of herb butter, or chimichurri are perfectly sufficient. The meat is the star – side dishes are merely the stage. Some meat lovers also enjoy eating dry-aged meat raw as carpaccio – pure umami delight!

The right core temperature

The key to preparing a good dry-aged steak is the core temperature. This is the most precise indicator of doneness. It should not exceed 60 degrees Celsius, but rather around 55 degrees Celsius. Rare steaks (approx. 50–52°C) and medium-rare steaks (approx. 55–57°C) are characterized by a more intense, meaty flavor, as more meat juices are retained.

At higher cooking temperatures, such as medium-well (65°-67°) or even well-done (70°-72°), the steak loses a lot of liquid and can become dry and tough. Furthermore, the muscle fibers are not as tightly contracted at lower temperatures, which ensures a particularly pleasant tenderness.

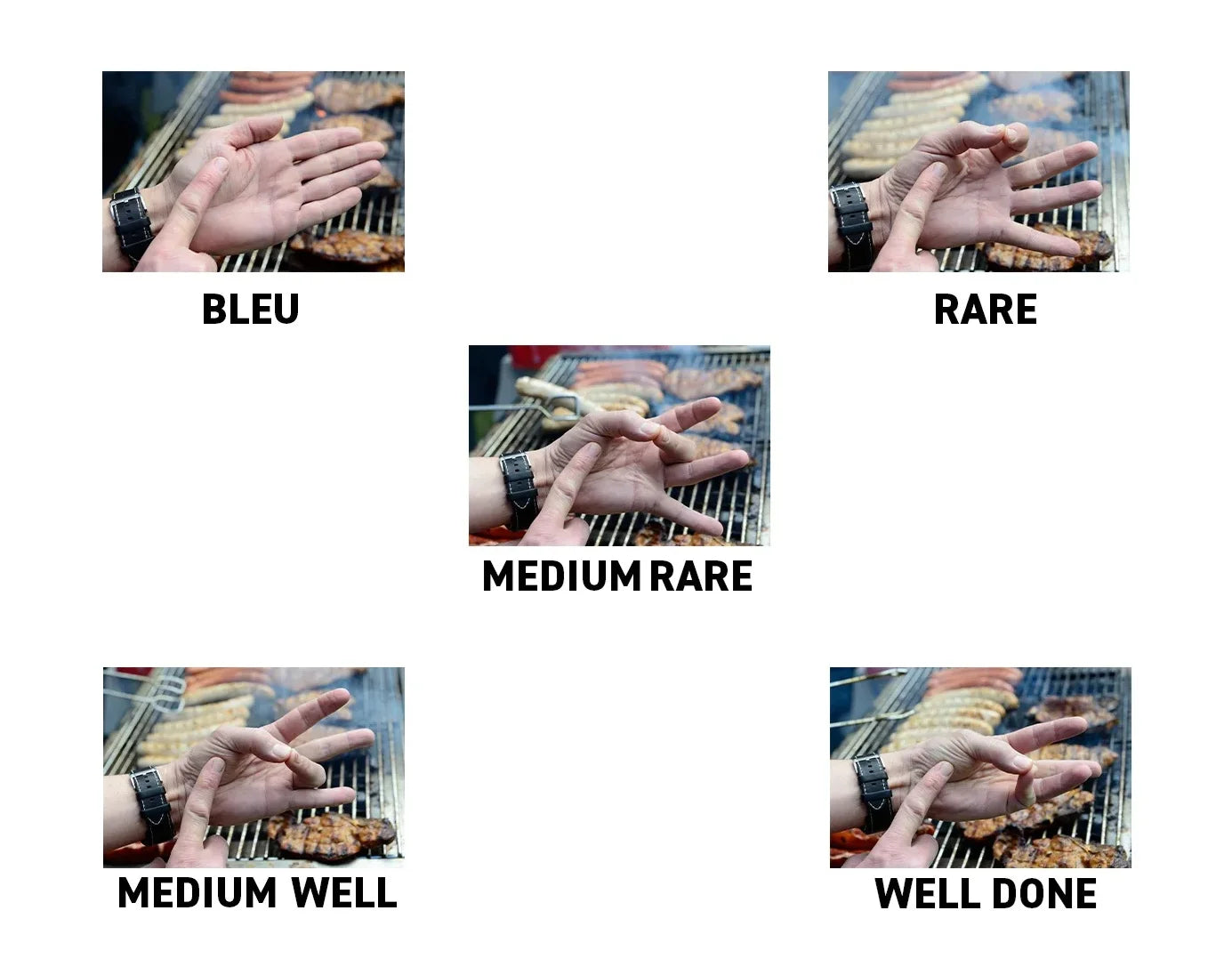

The finger pressure test to determine the degree of doneness

If you don't have a meat thermometer, you can also use the finger pressure test to assess the degree of doneness - although this method is somewhat less accurate.

By pressing the thumb together with the index finger, middle finger, ring finger or little finger, a tension is created in the ball of the thumb that varies from soft to firm, which corresponds to a certain degree of doneness.

Simply press your index finger into the steak, check the tension, and you'll know how cooked it is.

Many meat lovers ask themselves: Can you dry age meat at home in a regular refrigerator?

Dry-aging in your own refrigerator – is that possible?

Unfortunately, a standard household refrigerator doesn't provide the conditions necessary for traditional dry-aging of meat. Dry-aging meat is a highly precise process that only succeeds under strictly controlled conditions. A standard refrigerator can't guarantee these conditions over the long term.

The temperature for true dry aging must be constant between 0 and 2°C. Even slight fluctuations promote bacterial growth or can lead to spoilage. However, in normal refrigerators, the temperature fluctuates, especially due to daily opening and closing. Relative humidity is also crucial: It should remain constant at 80–85% throughout the entire aging process. However, a standard refrigerator does not offer the option of precise humidity control. Furthermore, consistent airflow is necessary to ensure the surface of the meat dries and prevent mold from forming. Household refrigerators, however, do not have targeted air circulation.

These factors make it clear: aging meat in a regular refrigerator is risky and endangers both meat quality and food safety.

Dry-aging refrigerators for the home

Those who want to experience true dry aging at home can now rely on special dry-aging refrigerators. These devices automatically control the three crucial factors – temperature, humidity, and airflow – thus creating ideal conditions for safe dry aging. This allows for an authentic aging process, otherwise only known from professional aging chambers, to be carried out at home.

However, keep in mind: A high-quality dry-aging cabinet costs about twice as much as a very good refrigerator and often takes up a similar amount of space. Not every household can easily afford this.

Get it now directly from our dry-aged shop!

How do you store dry-aged steaks?

Dry-aged meat should be stored carefully to preserve its distinctive flavor and high quality. It is best kept in a refrigerator at temperatures between 2 and 4 degrees Celsius. In a regular refrigerator, it is recommended to place the meat on the lowest shelf, where it is coldest.

Steaks typically last three to four days this way, while larger cuts can be stored for up to five to six days. If the meat is vacuum-sealed, its shelf life is extended to several weeks.

Dry-aged meat is also suitable for freezing without compromising quality. Ideally, the meat is already vacuum-packed and frozen (as supplied by Kauf Dein Steak); otherwise, you should vacuum-pack and freeze it yourself. Beef stays fresh for up to 12 months at -18 degrees Celsius. To thaw, it's best to refrigerate it to fully preserve its flavor and tenderness.

What our customers say

Jörg W.

This is the fourth time I've ordered dry-aged steaks from Kauf Dein Steak. It's a delight every time. Top quality and really fair prices. Lightning delivery. Ordered yesterday at 9 a.m., delivered today at 7:30 a.m. I'm thrilled with all of them. A dream!

Martina F.

We bought fillet and rump steaks . Delivery was quick and reliable. They also included some steak pepper . The quality is impressive! No water in the steak – dry-aged at its finest.

Sven W.

I can mainly comment on customer service, as I had the package sent as a birthday present. And the delivery was great. Everything went smoothly and without complications.

Animal welfare as a quality factor for dry-aged meat

In modern meat production, animal welfare is becoming increasingly important. Not only for consumers, but also for slaughterers and butchers. It's not a trendy buzzword, but an essential component of responsible agriculture and slaughtering. Dry-aging meat is a method that aims to intensify and improve the flavor and texture of the meat. But how the final product tastes and feels is influenced not only by the aging process. The animal's well-being and nutrition also play a crucial role in this equation.

The basis: health and freedom from stress

A high level of animal welfare begins with species-appropriate husbandry. Animals that have sufficient space, freedom of movement, and fresh air develop healthy muscles and an optimal fat percentage. Stress-free slaughter is also crucial. Stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline negatively affect the pH of the meat , leading to a tougher texture and less juiciness. Stress-free animals, on the other hand, produce tender meat that is perfectly suited to the dry-aging process.

Feeding and marbling

Nutrition has a direct influence on meat quality . A natural, balanced diet—such as grass, hay, and grain—provides fine intramuscular fat and appropriate marbling. This marbling is crucial for dry aging, as the fat acts as a flavor carrier during aging and provides the typical buttery and nutty aromas. Furthermore, a high-quality diet promotes a healthy fatty acid profile with more unsaturated fatty acids.

Ripening process and aroma development

Meat from healthy, well-maintained animals matures more evenly and has a lower reject rate. This is due to the more stable meat structure and optimal fat distribution. Dry aging enhances the complex flavors without the risk of premature spoilage. The result is an intense, full-bodied aroma that lovers of dry-aged meat particularly appreciate.

Animal welfare is not a minor matter

Animal welfare is the basis for our excellent dry-aged meat.

Only through species-appropriate husbandry, conscientious care, careful feeding, and healthy, stress-free animals can Kauf Dein Steak guarantee the highest level of product quality – a quality that can be seen and tasted.

The cattle are transported to the slaughterhouse using modern vehicles, using short routes, in accordance with animal welfare standards and with as little stress as possible – as befits responsible animal treatment.

Anyone who cuts corners on animal welfare is cutting corners – and you can taste it.

Animal welfare as a quality factor for dry-aged meat

In modern meat production, animal welfare is becoming increasingly important. Not only for consumers, but also for slaughterers and butchers. It's not a trendy buzzword, but an essential component of responsible agriculture and slaughtering. Dry-aging meat is a method that aims to intensify and improve the flavor and texture of the meat. But how the final product tastes and feels is influenced not only by the aging process. The animal's well-being and nutrition also play a crucial role in this equation.

The basis: health and freedom from stress

A high level of animal welfare begins with species-appropriate husbandry. Animals that have sufficient space, freedom of movement, and fresh air develop healthy muscles and an optimal fat percentage. Stress-free slaughter is also crucial. Stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline negatively affect the pH of the meat , leading to a tougher texture and less juiciness. Stress-free animals, on the other hand, produce tender meat that is perfectly suited to the dry-aging process.

Feeding and marbling

Nutrition has a direct influence on meat quality . A natural, balanced diet—such as grass, hay, and grain—provides fine intramuscular fat and appropriate marbling. This marbling is crucial for dry aging, as the fat acts as a flavor carrier during aging and provides the typical buttery and nutty aromas. Furthermore, a high-quality diet promotes a healthy fatty acid profile with more unsaturated fatty acids.

Ripening process and aroma development

Meat from healthy, well-maintained animals matures more evenly and has a lower reject rate. This is due to the more stable meat structure and optimal fat distribution. Dry aging enhances the complex flavors without the risk of premature spoilage. The result is an intense, full-bodied aroma that lovers of dry-aged meat particularly appreciate.

Animal welfare is not a minor matter

Animal welfare is the basis for our excellent dry-aged meat.

Only through species-appropriate husbandry, conscientious care, careful feeding, and healthy, stress-free animals can Kauf Dein Steak guarantee the highest level of product quality – a quality that can be seen and tasted.

The cattle are transported to the slaughterhouse using modern vehicles, using short routes, in accordance with animal welfare standards and with as little stress as possible – as befits responsible animal treatment.

Anyone who cuts corners on animal welfare is cutting corners – and you can taste it.

Conclusion

Today, dry-aged meat, due to its high value, is often served on special occasions or by discerning gourmets. It stands out significantly from industrial, wet-aged mass-produced meat. Its elaborate aging process, the careful selection of the best cuts, and the artisanal care it provides result in a product that is far more than just a piece of meat.

Dry-aged meat stands for tradition, quality, and incomparable flavor. Choosing this type of steak isn't just investing in exceptional enjoyment, but also in an experience that appeals to all the senses. It's the result of time, precision, and passion—and that's precisely what makes every dry-aged steak truly special.

We take the same approach here at "Buy Your Steak": We want to bring the traditional taste back to you and onto your plates with our modern, hygienically adapted methods. Eating is a pleasure, and we should consciously experience it – with all our senses, in every moment, with every bite.

FAQ

Dry aging explained simply – understandable, concise and to the point.

What exactly is dry-aged meat?

What exactly is dry-aged meat?

We explain what distinguishes dry-aged meat on our page Introduction to Dry Aging

Why is dry-aged meat so expensive?

Why is dry-aged meat so expensive?

We explain why dry-aged meat costs more in the section What’s special about dry-aged meat

How do you prepare dry-aged steaks?

How do you prepare dry-aged steaks?

The section “Preparing Dry-Aged Steaks” describes in detail the different preparation methods for dry-aged steak.

What is the best meat for dry-aging?

What is the best meat for dry-aging?

Discover in the section Best Meat for Dry-Aging which cuts are perfect for the aging process

Is dry-aged meat really better?

Is dry-aged meat really better?

In the section The Benefits of Dry Aging , we show you why many meat lovers prefer dry-aged meat.

Is dry-aged meat rotten?

Is dry-aged meat rotten?

You can find out why dry aging has nothing to do with decay in the section Decay vs. Maturation .

What temperature is used for dry aging?

What temperature is used for dry aging?

We tell you what temperature is required for perfect dry aging in the ripening chamber in the section Maturation takes time

Can you dry-age meat in the refrigerator?

Can you dry-age meat in the refrigerator?

In the section Dry-aging in your own refrigerator – is that possible? you can find out whether ripening is possible in the household refrigerator.

How do you eat dry-aged meat?

How do you eat dry-aged meat?

The best way to eat dry-aged meat is described in the section "How to eat dry-aged meat?" .

What does dry-aged meat taste like?

What does dry-aged meat taste like?

In the section Enzymatic Activity and Flavor Development , you'll learn how uniquely intense dry-aged beef tastes—and why it's considered a true delicacy.

Why doesn't dry-aged meat mold?

Why doesn't dry-aged meat mold?

Whether dry-aged meat molds or not, you can find out in the section Decay vs. Maturation

How “old” is dry-aged steak?

How “old” is dry-aged steak?

In the section “Aging Takes Time,” you’ll learn the secret behind the “age” of dry-aged steaks—and why it’s really all about aging.

What is special about dry-aged meat?

What is special about dry-aged meat?

You can find out what is special about dry-aged meat in the section What is special about dry-aged meat